U.S. National Park Service. Adult green sea turtle

U.S. National Park Service. Hatchling green sea turtle

Green sea turtle. Photo by Michael Lusk of the U.S. Fish and wildlife service.

Fact File

Scientific Name: Chelonia mydas

Classification: Reptilia, Order Testudines, Family Cheloniidae

Conservation Status:

- Federally Endangered in the U.S.

Size: 5ft long

Life Span: 75 years

Identifying Characteristics

The shell is broad and heart-shaped and the head is small. This sea turtle grows to a length of 91 to 153 cm and weigh 100 to 340 kg. The smooth, keelless carapace is brown with brown mottling. The plastron is white to yellow and the head is light brown with yellow markings. The flippers are paddle-shaped and each has one claw. The tail of the males is strongly prehensile, extends beyond the posterior margin of the carapace, and is tipped with a claw-like appendage. In females, the tail rarely extends beyond the carapace. The carapace of hatchlings and juveniles is brown to dark green and keeled. The undersurface is white, and the head and flippers are black. The limbs and all scutes on the shell are edged in white. This color pattern is an example of countershading, a means of being less visible to potential predators from above and below in the water. The breeding season varies with location but probably does not occur in Virginia. The incubation period is 48-70 days, depending on the beach conditions. Nesting occurs at 2, 3, or 4-year intervals. They have 2-7 clutches per season with 75-200 eggs/clutch. The female builds the nest at night on a sloping beach. She digs a large basin with the front flippers, and at the bottom of this digs a smaller hole with the rear flippers.

Habitat

The green sea turtle is found in shallow warm waters; where they forage for sea grass and algae. These turtles can often be spotted along the major oceanic currents as they use them for migration allowing them to traverse the vast ocean.

Diet

The green turtle has the unique ability among marine turtles to digest plant material. Hatchlings and yearlings are primarily carnivorous. Mature loggerheads feed primarily on vascular sea grass, but will also eat marine animals, particularly cniderians, mollusks, crustaceans, sponges, and jellyfish, whenever available.

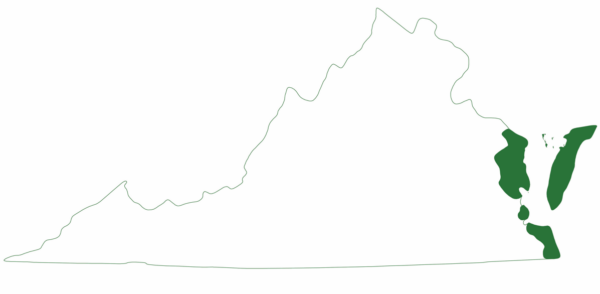

Distribution:

Only two live individuals have been caught in Virginia waters since 1979, one from the York River and one from the Potomac River. Six dead specimens have been found from the lower Chesapeake Bay, the Eastern Shore, and Virginia Beach. They prefer high energy beaches with sand deep enough to deposit the eggs below one meter. Juveniles live in Sargassum mats in major ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream. When not migrating, green turtles prefer sea grass flats which occur in shallow areas of the Chesapeake Bay.

Did you know?

Green sea turtles always travel in large groups originating from the same hatching day and beach to which they will return when it is time for them to lay their eggs

Role in the Web of Life

Green sea turtles play a vital role in their ecosystem as they turnover nutrients consuming algae and as they only consume the top of the sea grass leaving the roots alone they reinvigorate seagrass beds leading to a healthier plant as they encourage growth of new leaves. They also have a symbiotic relationship with the Yellow Tang which follows these turtles and consumes debris from their shells and body.

Conservation

Historically these turtles have had their skin used for handbags and their meat for turtle soup with their eggs being a delicacy. This consumption of green sea turtles was so large that several commercial farms existed which eventually closed due to international market regulations on the shipping of endangered species. As a species they were readily exploited in the 1700s and only recently have protections been enacted to prevent the hunting and poaching of these animals. Such as ensuring fishing nets are safe for marine animals, reducing light pollution on hatch dates, and attempting to mitigate habitat destruction and naturally preventing poaching for consumption.

Sources

Hersh, K. 2016. “Chelonia mydas” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed August 15, 2023 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Chelonia_mydas/

Fosdick, Peggy & Sam (1994). Last chance lost?: can and should farming save the green sea turtle?. York, PA, USA: Irvin S. Naylor. pp. 73, 90.

U.S. National Park Service. Green sea turtle hatchling. Padre Island National Seashore. https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/00B90B7C-155D-451F-67F22AA4A633089A

U.S. National Park Service. Green sea turtle on shore. Padre Island National Seashore. https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/00BB008F-155D-451F-6714D823EF32FAFA

Updated 2023 : Mara Snyder

Last updated: March 10, 2024

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources Species Profile Database serves as a repository of information for Virginia’s fish and wildlife species. The database is managed and curated by the Wildlife Information and Environmental Services (WIES) program. Species profile data, distribution information, and photography is generated by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, State and Federal agencies, Collection Permittees, and other trusted partners. This product is not suitable for legal, engineering, or surveying use. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources does not accept responsibility for any missing data, inaccuracies, or other errors which may exist. In accordance with the terms of service for this product, you agree to this disclaimer.